There are a lot of great t-shirts in Etsy stores celebrating Barbenheimer, the weekend of July 21st where two movies featuring big ideas and themes were released. I bought one and I can’t wait for it to get here.

But I happened to watch Knock at the Cabin on Amazon Prime a few days before seeing either blockbuster in the theater, and I wanted to look at a thematic connection between M. Night Shyamalan’s taut would-you-rather movie and Christopher Nolan’s historical opus. Big spoilers below.

Knock at the Cabin starred Jonathan Groff, the actor who played Mindhunter, then the upgraded Agent Smith in The Matrix Resurrections. As Eric in Knock, he transcended the previous roles (knower of humanity’s darkness and guardian of its ignorance, respectively) by offering his life to save a world he believed was worth saving.

Eric’s husband, Andrew, felt otherwise. He repeatedly chose to let the world burn if it meant he could keep the people he loved most. He would rather spend eternity alone with his husband and daughter than kill one of them to save a hostile, bigoted world.

My boyfriend and I were on his side. “Easy choice for us,” he remarked when we discussed the movie later. But then you’ve gotta be wary of the Twilight Zone irony of being isolated with the people you think you love so fucking much for the rest of eternity, roaming a wasteland of your own making, forever haunted by the responsibility of your selfish choice.

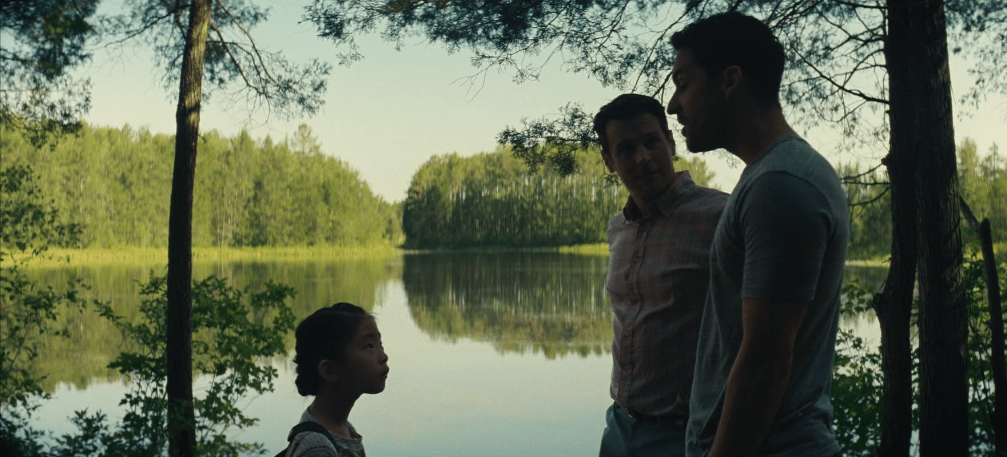

And so, skeptical of the Four Horsemen’s warnings, parts of humanity were judged by the couple until the very last minute where a vision of joy and love emanated from Eric, anchoring his previous ambivalence into decisive action. In his vision he saw his husband, older, taking their grown daughter to dinner to meet her new partner – someone who loves her and who she loves just as much. Eric was willing to die to save this hateful world, for his daughter to have a chance to love someone as much as he loved and was loved by Andrew.

Never mind the malicious nature of a God who would play such a game with his own children. The movie sidesteps that whole question completely. God’s just a writer with a dark, cruel curiosity who wants to see if his creation should just get wiped from the slate. Give the characters agency, let them decide. Have you finally had enough? Should we just pull the plug?

So now let’s talk about Oppenheimer.

Here was a man partly responsible for unleashing the plague of nuclear proliferation upon us, but who carried the guilt of his responsibility very differently from other players like President Truman. Oppenheimer wanted to mitigate the usage of the massively destructive power he brought to mankind, while mankind insisted on having immediate access to that power, crushing its visionary creator in the process.

To me it affirmed my position alongside Andrew, of “Fuck ‘em. Let it all burn.” As if I could say, “Don’t sweat it, Oppi. They want to destroy themselves. Look at how petty they are! They kind of deserve it. They just used you to get closer to that goal.”

Clear that I’m missing a few screws in this imaginary interaction, he would slide deeper into resigned acceptance of his martyrdom; his superposition as Destroyer and Savior collapsing into a certainty of one and not also the other.

In the end it seemed that Oppenheimer could not unsee himself as a destroyer; to assure himself of his savior status would have felt like a filthy delusion after the crushing inquisition Lewis Strauss orchestrated against him… And maybe also after the apparent suicide of his lover Jean Tatlock.

In trying to save humanity, he plunged it into a new danger. Unforeseen consequences. The harsh light of hindsight. Up or down the scale, none of us are immune.

My biggest issue with Knock at the Cabin – apart from the character of a god who likes playing the most sadistic would-you-rather game ever – was that if Andrew had been right about the home invaders being crazy and the news stories being faked and timed, but had bought in before it got really weird, the survivors would never have known if it was real or a delusion.

Of course, with someone they loved more than the world itself dead and the world spinning on, they would likely convince themselves that the threat had been real enough to justify the choice they made. In the alternate ending where my boyfriend and I would choose to let the world burn, justification of our choice would be impossible – even though he’s awesome and I would rather spend the rest of my life alone with him than have to deal with with rest of the world without him.

This path is for those who have decided that People = Shit. Champagne for my real friends and real pain for my sham friends. It’s a narcissistic choice, even a little psychopathic, maybe, but relatable. Victims who become villains are common as dirt, justifying our petty hatred by recalling the harm done and feeling it right to punish or even eradicate the cause of past pain.

It seemed that Oppenheimer never once took this position – not even as a handful of people turned out to be vindictive, judgmental turds intent on destroying him. Instead he seemed humbled, accepting of the phony condemnation orchestrated against him, withering away as he lost all his world-changing charisma and power, succumbing to throat cancer – an affliction of his Vishuddha, the chakra concerned with having a voice to speak truth to power.

I’m struggling to close this essay, so I just want to point out one last thing before I go: Rami Malek’s character, David A. Hill, was such a beautiful counter example to Robert Downey Jr.’s wicked Lewis Strauss. Such clear-sighted individuals as Hill – who can see past the ego slights that just roll out of personalities like Oppenheimer’s – are extraordinary and worth preserving humanity despite all its Trumans, Tellers, Strausses, and Robbs running around unchecked. (Not that people are either/or, because I have experience in the roles of both.) Oh, and audience avatars like the senate aide played by Alden Ehrenreich – who did check Strauss – are obviously worth saving, too.